You re Spinning Me Around in Circles Again That Cute Skinny Blond Girl

"It felt similar being function of this secret in Detroit that shortly the whole world was going to know about." — Tommy Valentino

When Child Rock kicks off a sold-out, ten-show stand up Friday at DTE Energy Music Theatre, he'll roll out a set of familiar hits and stage moves — the cloth he'due south fabricated famous since his national breakout in 1998.

Just as virtually Detroit fans know, there's far more to the Kid Rock saga than that.

By the time his x-evidence run wraps up, he'll have played to 150,000 hometown fans. Why is Kid Rock so big in Detroit?

Because Kid Rock got a caput start in Detroit: a decade of edifice his name, grooming his sound and reinventing his persona from scrappy hip-hop street kid to swaggering stone-rap showman.

This year brought a new career affiliate: Rock'due south album, "Outset Kiss," marked his departure from Atlantic Records, the company that launched him into the national spotlight with 1998's ten-million-selling "Devil Without a Cause."

Getting to that point wasn't without struggle. The teenage Kid Stone had been dropped by his first label, and he returned to Detroit in the early '90s disillusioned but determined to make information technology on his own terms — driven non by coin but by an intense thirst for fame.

Here'south a wait back at those early Detroit years, 1990 to '98, when a young Bob Ritchie hustled hard to go noticed — and molded himself into the Child Rock the rest of the globe knows today.

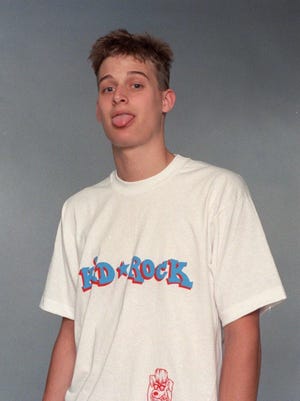

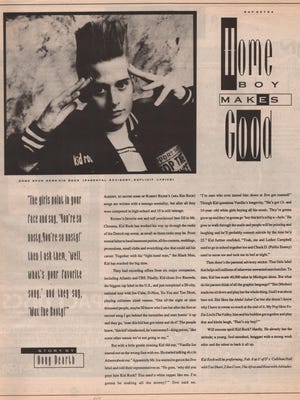

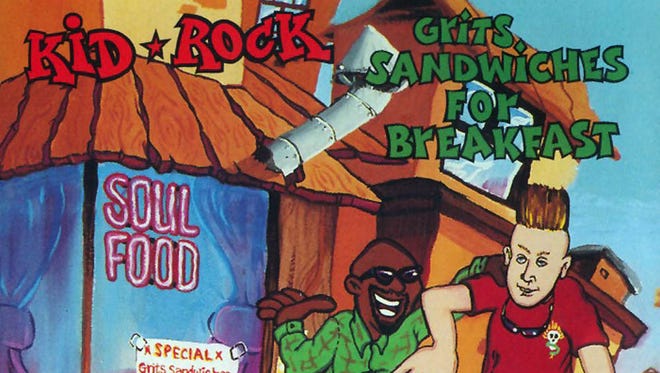

Romeo-born Ritchie was a little-known 17-yr-old rapper and DJ when he was signed past the New York hip-hop label Jive Records, which issued his 1990 debut album, "Grits Sandwiches for Breakfast." He'd spent his teen years playing e side firm parties and making connections on Detroit's fledgling hip-hop scene, and "Grits" was his Beastie Boys-inspired record of earthy, boasting rap.

Jive booked Kid Rock on that year's Straight from the Secret parcel tour with Likewise Brusk and others — a shot at a national audition.

But his Jive stint was brief, and the young rapper was before long back in Detroit plotting his next move.

It would exist the fundamental stage in Kid Rock's evolution, as his hair grew longer, his music grew louder and his live show grew bigger.

MIKE E. CLARK (producer-mixer): I cutting his demos as a kid earlier he got signed in 1989. I was working with generally young black teenagers so. I didn't know he was white — we caught each other off-guard when he came in. I idea, "Yeah, certain. A white guy is going to rap." But he shut me up. He had his turntable, had his beats, his stuff already written. He had his shit together and blew me away.

He was very confident, had the high-top fade, very sharp. You could tell right away he wasn't bullshitting. He had a shitty little Casio keyboard, and knew exactly how he was going to practise it.

He took those demos and got a deal with Jive.

JOE NIEPORTE (director, the Ritz, State Theatre): I ran the original Ritz in Roseville, an 1,800-seat venue. Very big. He wanted a gig. He came in pretty cocky: "I'm going to fill up this place." Every band I talk to says that. Merely he had a lot of wits virtually him. Merely a potent, cool personality.

We did the gig and he put 1,200 people in at that place. I was diddled away.

He had a great street squad, a lot of footling kids helping him back so.

JERRY (VILE) PETERSON (publisher, Orbit magazine): He had this giant Mt. Clemens posse. The high school friends. You lot'd meet then many of them at once.

NIEPORTE: Bob was just straight-upward rap and so. He didn't have a band. You've heard that early stuff — a lot of profanity, real edgy, hard-core. I wasn't a big rap fan, but I liked his stuff. But I remember telling him, "Dude, if you're going to brand it to the next level, you lot've got to clean information technology up."

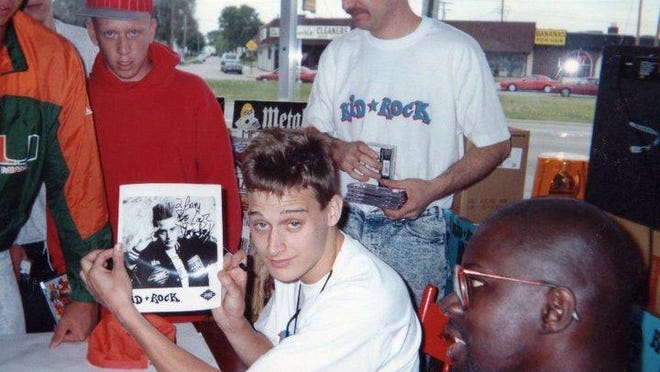

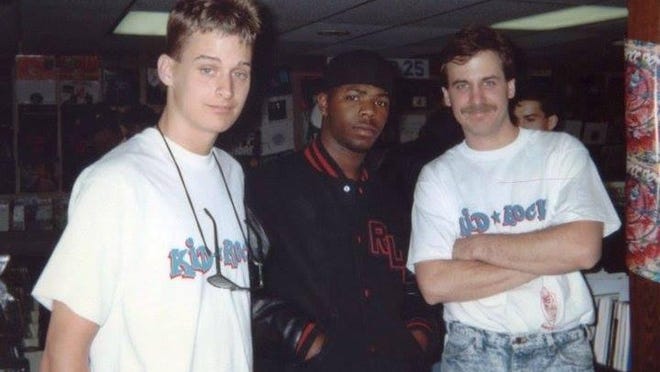

MIKE HIMES (owner, Tape Fourth dimension shop): When "Grits Sandwiches" came out, he came in for an in-shop (performance) at 10 and Gratiot. He had the tall hair, spinning similar he would at the bars in Mt. Clemens. We had a decent turnout. Toward the end, this blond-haired skinny child kept yelling out — "I'll battle you lot! I'll battle you!" Just persistently getting in Kid Rock's face up. I came up to him: "Dude, this is his day, his outcome. Maybe one solar day you'll have your day, simply get out the guy solitary." He followed him out to the parking lot still wanting to boxing.

That was Eminem. He gave him a couple of his tapes: "Cheque me out." At least Kid Stone was cordial about information technology.

CLARK: (In 1990) Vanilla Water ice came out and stunk things upwardly. So Jive decided they didn't want a white rapper anymore. They couldn't see the future, and they dropped Child Rock, which was devastating to him. He got a bargain with an independent label, Continuum, and said, "(Screw) it, Clark. Let's exercise this tape." We worked on "Polyfuze Method" at the (Ferndale studio) Tempermill in '92.

With Jive, he tried to be the rap guy, keeping it all hip-hop. But — and this is but my opinion — he got disillusioned by existence dropped. And so he was like, "(Spiral) it, I'1000 going to do my ain thing."

TOMMY VALENTINO (music attorney): His mental attitude at present was, "I'm not going to count on whatsoever record company to brand me a star."

PETERSON: The whole Vanilla Ice comparison, he dreaded so much. It was a source of shame in that whole matter. In his commencement interview (with Orbit in 1990), he was saying he's not a Vanilla Ice, that he was trying to be the real bargain. And he always told me it was his parents' music that influenced him. Definitely Seger, which was like one-time-people music at that fourth dimension.

"The Polyfuze Method," a heavy, frenetic record, was released in summer 1993.

CLARK: We were calculation rock guitars, sampling Pink Floyd, whatever crazy stuff. At i point we had a flute player come in. Nosotros just didn't care.

He liked all kinds of music. When he goes to brand music, he does what he thinks sounds adept. If that was mixing a flute or heavy metal guitar on top of 808 drums — as long every bit it sounded good, that's what he did.

NIEPORTE: "Polyfuze Method" had a great rap presence, but as well brought a potent rock feel. When I heard information technology, I idea, wow, this guy is on to something. And he toned it down (lyrically). Not a lot. But he did tone information technology downwardly.

HIMES: It was his crossroads record: the hip-hop influence, merely starting to lean toward rock.

DAVID LEE (friend): The fact that he's now associated with so many genres of music isn't a surprise. Even though we looked at him every bit a hip-hop guy after the Jive thing, yous could start to meet those other elements — the rock 'n' roll, the country.

BRIAN PASTORIA (drummer, rock band DC Drive): I call up Bob coming to a bunch of our shows at the Ritz in the early '90s. Our singer, Joey Bowen, liked the Beastie Boys, so when nosotros did "You Need Love," we'd have this big breakdown with Joey rapping.

Bob knew he couldn't keep going downwards that Vanilla Water ice path. It got him attention at start, but he realized that's not where he wanted to be. He was tired of the rap thing with programmed tracks. He wanted to exercise the Beastie Boys thing — only in a bigger, more than rock kind of way.

Kid Rock was fighting for a name on the scrappy Detroit hip-hop scene of the '90s, amongst acts such every bit Insane Clown Posse, Esham and Eminem.

In summer 1993, Rock's ex-girlfriend gave birth to his son, Robert Ritchie Jr., who became known to anybody as Junior. Later that twelvemonth, Rock constitute his fashion to White Room Studios in downtown Detroit, run by brothers Michael and Andrew Nehra — rock musicians and so forming the rock-soul band Robert Bradley's Blackwater Surprise.

Rock cut tracks for his 2nd and terminal Continuum release, the "Burn down It Up" EP, which featured the rock-heavy "I Am the Bullgod" and a new country twist: a gritty cover of Hank Williams Jr.'s "State Boy Tin can Survive."

Rock soon launched his own label, Meridian Dog Records, and kept himself in local record racks with his "Bootleg" cassette series featuring new tracks and reworked material.

BOB EBELING (drummer, engineer): We were living together (in Sterling Heights) at possibly his lowest point. He had lived with (girlfriend) Kelly. At that place were 3 kids, he thought two of them were his, and so he found out that one of them wasn't. He was really emotionally torn up, going through that deep heartbreak stuff.

They divide and that'due south when I moved in the apartment. He was likewise kind of disenfranchised from his dad at that betoken. At that place wasn't a lot of financial back up coming from the family. Then he was probably nigh lonely at that point — existence heartbroken and away from his family and being on a smaller characterization like Continuum, non getting as much financial back up.

Just the one thing that was still there: He was motivated past fame. I've worked with five or six pretty large stars — Eminem, Rufus Wainwright, Phish — and there's a sure archetype personality that only needs to be famous. Fame is quite an ugly thing to me, and most people would exist scared to expiry of information technology, only he was driven by it. He talked about information technology in ways that didn't even make sense to me. He relished it.

He loved when we went somewhere to swallow and somebody recognized him. He had this whole reward organisation in his caput that didn't exist in other people's heads: When people recognize yous and want a piece of you, it was the equivalent of being wealthy. He just ate it upwards.

AL SUTTON (White Room co-founder, engineer): We were the grunge, difficult-stone studio. Bands came in with amplifiers, guitars and drums. And in walks this guy with a sampler and MPC60.

He started hanging out in the studio. We needed somebody with his skills in our army camp. He could program and loop, and we needed to be a fiddling more electric current in that way. Nosotros had a B-room that he basically took over, coming in midday and staying 'til five in the morn.

MICHAEL NEHRA (White Room owner): Andy (Nehra) and I were a conduit for his creativity by giving him a studio to use. We worked with him in coproduction, technology, some writing stuff. Bob was really fun to work with back so. He was creative, and nosotros were all really good friends. We gave him the keys to the studio later the Continuum thing, and he created a lot of absurd stuff there. There was this energy between the ii rooms, creating music.

SUTTON: He was cleaning all the time. He's a real great freak, had to accept his place actually tidy. He'd vacuum the B-room and so get to work.

Nosotros idea he was adept energy to take around. If nosotros needed something programmed, he'd be here; if he needed a guitar office or drums, we could set up it up. It became this symbiotic relationship.

JIMMIE BONES (keyboardist): He was this guy that was e'er effectually, his Dickies and stocking cap on. He started asking me to come in: "Hey, I'k doing a track; tin you throw on some piano?"

NEHRA: He was learning from my brother and I. We were at that place playing the guitar and bass on "Bullgod." Bob wrote the song, only my brother and I fabricated it audio like "Bullgod." Bob could play some guitar, only my blood brother and I were rock 'northward' rollers who played the groove thing with Robert Bradley, and that energy certainly rubbed off. When he starting time came into the studio he didn't really sound like that.

He was starting to get more of a rock edge, and that'southward what we tapped into — that stone 'northward' roll spirit, that Detroit soul thing.

CLARK: The first time I ever heard him sing, E Detroit had recently changed its proper name to Eastpointe. And so Bob changed the lyrics to Billy Joel's "It's Still Stone and Roll to Me" to record a cover version called "It's Still Eastward Detroit to Me." He started singing, and I was like, "Dude, you sound amazing!" He was just (messing) around, but he sounded really proficient. I could hear the tone. He could hitting the notes.

When "Only God Knows Why" became a large hit later on (in 1999), he looked at me and said, "You know, you were the first (person) who told me I could sing."

PETERSON: We'd have these Orbit karaoke nights, and that'southward when I learned he could actually sing. He'd do "Stayin' Alive," all the parts. Plus he brought the mushrooms, which made the karaoke even more fun.

HIMES: He was hustling, coming in on a regular basis to drop off his (tapes and records) on consignment. He had flyers for his shows, tickets for the DJ things he was doing. He already had a vision. He was promoting himself, trying to meet the right people. We'd sit in the store and he'd ask me questions at length — where to get records pressed, that kind of matter. He would pick your brain, simply thirsty for information.

SUTTON: He was killing information technology on the piffling tapes he was releasing, selling a ton of his own cassettes out of the record stores and his machine. And he was making good coin playing gigs.

But Bob wasn't getting a lot of credit from the hipsters and rock scene in Detroit. It was, "Oh, he'southward a white rapper; no need to accept him seriously."

Marker BASS (producer, Eminem): He was innovative, e'er a few steps ahead of what hip-hop was doing. Just hip-hop didn't want to hear it, considering he was this white guy with the long rock hair.

SCOTT LEGATO (photographer): I was a DJ, spinning rap at the Struttin' Society on Gratiot. He showed up with his records. I blew him off. Showed up again; blew him off. Third time, I owed him. And then I put it on. The possessor immediately ran in yelling, "Accept that shit off!" I stopped the record. Kid Rock walked upwards and said, "Y'all're an asshole. Give me my records back."

CLARK: I call up ICP fueled Bob a lot. He wasn't a large fan, and when he saw these guys selling out the State Theatre, information technology threw gas on his flame. They really didn't become forth. I was the guy in the middle: friends with Bob and working with ICP.

He was tenacious: "OK, that matter didn't work; allow's try this or that." And he kept gaining fans around town. He had the talent. He merely needed to figure out how he could make other people realize he was a forcefulness to be reckoned with.

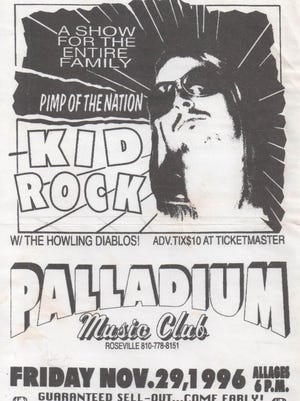

NIEPORTE: He'd go to every high school around here and pop his trunk open when school allow out, handing out free samplers. Back so, all-ages shows didn't really be. It was 18 and over, headliners going on at midnight. So Bob comes in, promotes his shows as all-ages with early starts, and he'due south getting ane,200 kids in there.

He drew from all over (metro Detroit), but predominantly the east side. He was from Romeo, and he had cut his chops in Mt. Clemens, so those were his roots.

UNCLE KRACKER (friend, DJ):He built a following. He'd play the Majestic or the Ritz, then bounce around back to (smaller venues like) Alvin'southward or St. Andrew's. He would play once every vi months or so — get in look like he was coming through on tour equally opposed to chirapsia everybody in Michigan over the head every weekend. He was very smart about that whole supply-and-need affair.

You'd take 900 people in the room — all these little white kids who dropped acid and liked listening to gangsta rap.

MARC KEMPF: (hip-hop manager, promoter): There were (hip-hop) scenes developing at the Hip Hop Shop and St. Andrew's Hall, the "2 Floors of Fun." Just he was a maverick. He was doing his thing. He wasn't part of another scene, coming upward with other artists.

BASS: With Bobby's matter, he didn't have to fit in the same way Marshall (Eminem) did. Marshall was on that secret hip-hop, kind of edgy, street level. Bobby was likewise on the street level — just a different street with nicer lights. (Laughs) When yous saw Kid Stone onstage, information technology was such a show that it was more of an alternative-rock thing.

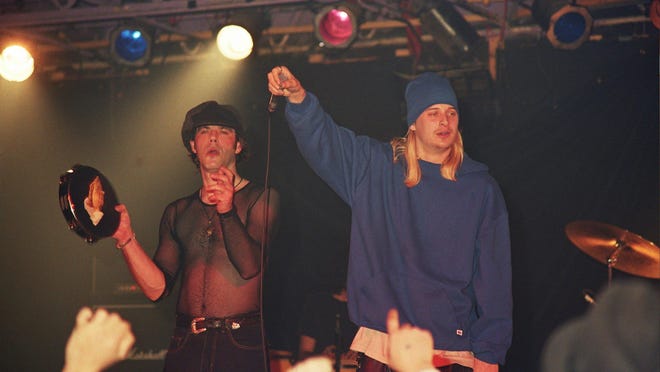

In 1994, a festive Sun music scene was emerging at the Deport's Den in Berkley, led by the funky, eclectic Howling Diablos. Rock became a weekly regular, and many have cited the Diablos' rapping, fedora-topped front homo Tino Gross equally a big influence on Rock's onstage style.

His shows to that bespeak had been a standard rap setup — Stone rapping, Uncle Kracker or DJ Blackman on turntables — just now he was assembling a revolving group of stage musicians to join him. He adopted a ring name that endures today: Twisted Brown Trucker.

TINO GROSS (Howling Diablos): Bob's sister Carol was a cocktail waitress, and she told him virtually us. He told me later, "I figured if she liked you, it had to be wack, because she's my older sister. Man, was I wrong."

There was some magical free energy going on in the Behave'southward Den. It was this existent organic hugger-mugger thing, all about the music. A lot of things came together there, and Bob was a big office of it. He'd come in right backside us with his turntables and record crate. He'd scratch with us, and subsequently a while, I was giving him the mic. He'd be our toaster, rap some stuff, sing the choruses together. The Diablos' mentality was like jazz musicians — anything tin fit in.

He had been doing these all-ages shows around town, where parents dropped off their kids in the middle of the afternoon. At present he was trying to grow his brand and reach older people more into rock and blues, beyond the limited immature hip-hop crowd effectually Detroit.

BRAD SHAW (Kid Rock photographer): The Howling Diablos were good, and he got a lot of ideas from them. Tino is such a not bad showman, and the whole ring are such great players. Bob was down there every Sunday dark.

I'grand sure he got a lot of this and that from them, there's no doubt. He put that in the back of his head. He was always about the funk and rock 'north' curlicue anyhow. He knew his hometown stuff. He was aware of everything, from Seger to Alice Cooper.

Basic: The Bear's Den thing was a real melting pot vibe. It would start with the Diablos, then simply a big jam after that, where all these players are coming up. That played a big role in making Bob known. He could get up there and freestyle and put that into a jam state of affairs. It helped him cross over to maybe some folks that wouldn't accept taken that (rap) genre very seriously, or weren't all that knowledgeable about it.

CLARK: Bob was fascinated by all that. The fact that they could put on a live show and captivate an audience — that was inspirational.

GROSS: A lot of people will tell you he got a lot from the Howling Diablos, that's true. For me to say it, information technology sounds weird. Only nosotros were older, and he was a young guy soaking it in. Ideas were flowing on that scene. Our matter was probably the closest to what he ultimately ended up doing.

There were many times Bob said, "You guys are going to exist the next big wave out of here." He was very much a supporter. Then it wasn't like, "I'm taking their thing and running abroad with it." It was an overlapping, organic affair.

KRACKER: I started DJing for him (in 1990) when I was notwithstanding in high schoolhouse. My first gig DJing for him, I had simply gotten my license.

He figured out he could start playing bars in other cities if he had an actual backup ring too. Nobody was going to book him with just the track matter backside him. So he started putting together a grouping.

GROSS: I call up he saw with us how it works to rap over a alive band. He could see it and feel information technology. Sometime effectually the Bear'south Den period, he decided to put his own matter together, similar to what we were doing, and he created a band.

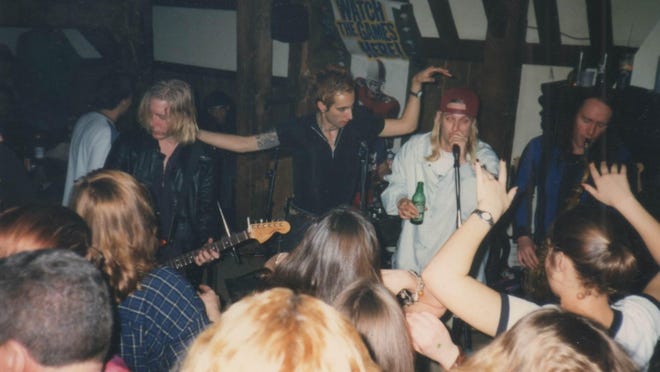

EBELING: The beginning big concert with the band was at St. Andrew's, former in the late autumn of '93. That was the first incarnation of Twisted Brown Trucker, though it wasn't chosen that just yet.

BONES: That idea also came from Public Enemy, (rap acts) like that who were using live stuff. Chuck D had started running live bands. The Beasties too. Those guys had a huge influence on him.

EBELING: He was very interactive in his evidence, constantly changing up the sequence. We were just blasting through all the material. He was very involved in how to dispense the energy of the crowd — lay back for a while then bring it up. He had the whole thing orchestrated, orchestrating the band and the background sequence.

NEHRA: He was experimenting with different musicians. There was this circle of people around Detroit. It wasn't the Jack White circumvolve. It was this unsung, not-quite-so-hip motion that was going on.

EBELING:In 1994, we booked a couple of weeks on the road, odd dates in Sarnia, around Iowa and Ohio, some of the colleges. Nosotros went out and did these half-assed gigs in front end of 20 people, sometimes five. If it was closer to home similar Toledo, it would be pretty packed, a couple hundred kids. And every time we were dorsum around Detroit, information technology would be a total house.

You were definitely feeling the struggle of information technology all, unless we were home playing the Palladium or Ritz — 2,000 kids, $ii,000 in merchandise, $forty,000 at the door.

It's nearly impossible to rails all the early variations of Twisted Chocolate-brown Trucker. There was massive turnover. That's because (ring members) were saying, "OK, I'chiliad non actually getting paid from this, and he is."

VICKIE SILER (Toledo fan): I was in my early 20s. I was mostly a rap fan, only I still loved hanging out with the drunk uncles listening to classic rock. When I saw Child Rock, I was like, "Well, that'southward it!" The first time was in '93 at the Primary Event in Toledo. Information technology was $5 or $vii. My friends were more excited about ICP playing in town that same night.

I could tell he had a voice like Rage Confronting the Car — that harsh rocker voice — along with his rapping skills. Only this crazy dude. He had that self walk to him, the existent pimp affair.

I worked as a stripper. I used to tell my girlfriends, "Allow'due south get run into that rapper dude Child Rock." He'd take the turntables going, some background beats, property a microphone. Stripper music, I called it. That blast-boom bass, where y'all could feel it. It was muddy, dingy, nasty, only some kind of fun stuff. We'd go to the show and dance, then become back to work.

GROSS: I did an interview with Dr. John on my blues radio evidence, and he went on and on about the midgets who were a large role of the New Orleans rhythm-and-blues scene, the whole carnival matter down at that place. I gave Bob a record of that show to listen to on a road trip.

Joe C had already been showing upwards at Bob's shows as a fan. Being the guy he is, Bob doesn't miss a play a trick on. After that, he looked out at Joe C one night and a light bulb went off.

Joseph (Joe C) Calleja was a 21-year-former Taylor resident who stood 3 feet, ix inches, his growth stunted past the coeliac disease that later took his life. Joe C became an onstage staple of Rock's concerts, a dynamic, popular, dirty-mouthed presence. He was part of a live set that would eventually get honed with a calorie-free show, pyro, dancers and a low-cal-up "Kid ROCK" backdrop.

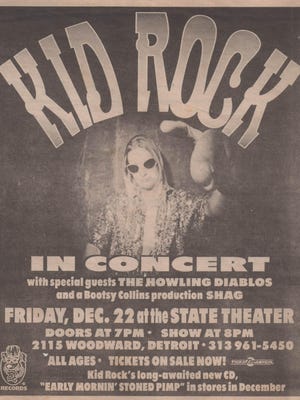

NIEPORTE: I left the Ritz in '94 to run the State Theatre (in Detroit). I wanted to volume Bob in that location, and in that location was some worry that information technology was too big. I really put my donkey on the line. It was the first Country show he did with Joe C and Uncle Kracker, and nosotros ended upward with well over 2,000 people.

GROSS: Information technology was such a showbiz matter. Joe C made the band more heady. Bob was trying something new onstage, different people coming and going. Merely Joe C just stuck. Onstage, it was a cute thing.

At the Detroit Music Awards (in 1997), we played with Bob. Ted Nugent was on the radio the next twenty-four hour period ranting: "This Child Stone character had a half-dozen-year-old male child upwardly there. Information technology'southward just non correct!" Child Rock merely smiled and gave me a thumbs-up.

LEE: There was a family atmosphere around Bob. When Junior became the same size every bit Joe C, he could never understand why Joe C got to do stuff like see the street, drink beer, leave with the adults. It was always hysterical.

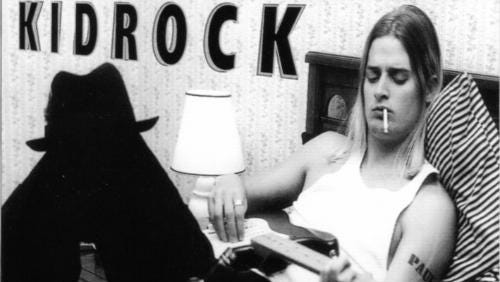

In 1996, however working at White Room, Kid Rock released his nearly rock-oriented record yet, "Early Mornin' Stoned Pimp," joined past a host of Detroit musicians that included Gross and the Nehras.

"I e'er wanted guitars and alive stuff. And that comes with money and connections," Rock told the Free Press at the fourth dimension. "Then I've tried to environs myself with talented people that I get forth with."

EBELING: Bob just has this unreal constitution that can keep partying. That's the last fill-in-the-bare of "how to be a rock star." He can party for three days straight. You lot'll wake up that 4th day and feel like dying. He snaps out of bed ready for the political party to keep going. And it's not that he's cheating — he's as drunk and stoned every bit anybody else. He'due south got something in his genes.

One morn, nosotros both woke up at the flat after a couple hours of sleep. He was revved upward and ready to proceed that level of insanity. And information technology just came out of my rima oris: "Dude, you are the early on-morn, stoned pimp."

THORNETTA DAVIS (R&B vocalist): He was hanging out at the White Room a lot and then. I sang on a couple of things on "Early Mornin' Stoned Pimp." He was showing us what to sing, and I said, "Wow, yous've got a voice — you're non just a rapper!" And lo and behold, he's a vocaliser now.

He wanted me to exercise a lyric that was pretty risqué. I'm similar, "I have a picayune daughter; tin can you not publicize that I'm on the album?" Certain enough, it comes out, and I'm on the credits. (Laughs)

EBELING: He was gaining momentum with "Early Mornin' Stoned Pimp," had his whole Detroit posse going, and stabilizing the band with the final lineup — Kenny Olson and Jason Krause on guitar. He had Joe C up there, starting to get the terminal elements of how information technology was going to look. Information technology was becoming the well-groomed show he would (later) tour with.

SHAW: He played the Club in Toledo around that time, and began the routine of changing into his pimp getup. He'd run offstage back toward u.s.a., tearing his clothes off. There wasn't much fourth dimension. You've got a guy throwing on a '70s pimp outfit — it was hysterical and difficult not to laugh.

He'd get dorsum out in the pimp outfit with a gun down his pants. And it was a real gun. (Laughs) You'd have to ask him if information technology was loaded. It probably was.

PETERSON: He was just a lot of fun to exist with. If y'all went to the strip bar with Bob, you'd have dancers sitting all over. In those days, it was hanging out at Garfield's or strip bars. When you went out with Bob after he started getting some money, information technology was keen. Always crazy fun.

LEE: It's well known that a lot of partying was going on. Nosotros were all rolling around Detroit for a few years. Nights would turn into days pretty fast. The bars, the hundreds of beers, the chicks. He was just a cool, fun guy to be around.

Simply that shouldn't overshadow the fact that Bob was deadly serious about ii things: raising Junior, and his career.

BASS: The partying just added to the whole thing. Same thing that made Mick Jagger. He was never out of command. He was ever a great businessman, a marketing genius.

SHAW: It was never about laying around getting stoned, thinking he's a rock star. He was constantly request, "What tin I practise to top that?" He was ever going a step ahead of the concluding show.

He'd call at 3 in the morning: "Dude, I'll meet you at the White Room in an hour. I've got a stripper to aid with a photograph shoot."

LEE: Bob and his boys dressed a piddling different — the windbreakers, amorphous pants, loftier-tops. We would accept them to hang out in certain rock 'n' gyre establishments, and non but did they stand out, we were sometimes told they weren't welcome.

GROSS: Memphis Smoke (in Purple Oak) was actually pushing the Diablos to do a show. We knew we were too wild to be in there. But we start playing, Bob shows upwards and gets up there rapping. Fun night. I get back in the manager's part, and he reads the riot act. "What was that blond asshole doing onstage with you guys? Don't always bring that shit around hither once more. Yous guys don't demand that!"

That sound had non been on the radio nonetheless. And they saw rap every bit some garbage music that was for stupid kids. Nosotros knew it could piece of work. To me, it was similar punk rock — we were building our own scene, and not everybody was downwardly with it.

SUTTON: One of the records coming out then was Alanis Morissette'due south "Jagged Lilliputian Pill." A lot of rock guys didn't like that album — it was programmed, had the drum machines. We were hanging out with a guy saying it sucked. Bob said, "Y'all don't know what y'all're talking about. That record is going to exist huge." Bob was totally on it. He saw the writing on the wall, where music was going, and he totally grabbed that.

JOEL MARTIN (owner, 54 Sound): This kid was doing something with the Internet that others weren't hip to yet. His small house in Purple Oak was similar a crash pad and record visitor. When I saw the performance in his basement, it blew my heed. The mailing lists, the street teams. He had a crew of people working the computer, doing things that at the time were really foreign. He understood at the very beginning what the whole Internet matter was about.

SUTTON: I was impressed. A young dude in music, already ownership a house. Not likewise bad. He had interns that would come up in from different states. It was hilarious — some kid flying in from California to make flyers for a couple of months. Bob always worked like he was a superstar.

Alongside director Steve Hutton, the New York music chaser Tommy Valentino was now aboard the Kid Rock team, and the pair helped foster buzz outside Detroit, including key stories in the Beastie Boys' Thousand Royal mag and the trade publication Hits. In 1997, they finally snagged the attention of a big record-biz exec: Jason Flom, head of Lava Records, part of the powerhouse label Atlantic Records.

SUTTON: We were at a restaurant in Royal Oak, a bunch of united states hanging out, and he said, "Man, my side by side record … I've come up upwardly with this matter. I'm going to practise a redneck, shit-kicking rock 'n' coil rap band." Everybody was laughing — "So that's information technology, eh?"

VALENTINO: I flew in to see him at the State Theatre (in 1996). I was blown abroad past his performance, how packed the place was, and the diverseness of the people there — everything from bikers to strippers to in between. Younger, older, from different backgrounds, all of them into information technology. At one betoken a woman threw a bra onstage, and I'm thinking, "This is an old-fourth dimension rock 'n' scroll bear witness!"

Steve Hutton and I were shopping Kid Rock together (to record labels). No one was interested: "White rap isn't what'southward in right now." They weren't getting it. It was frustrating. I kept saying, "He's not a white rapper. He'south a stone star and everything in between."

I really felt that if someone just saw the live show, they were going to sign him.

JASON FLOM (Lava/Atlantic Records, 2003 Gratuitous Press interview): Andrew Karp, an A&R guy for Lava, went to run across him in Cleveland at a place called the Grog Shop. He told me, "Hey, there were simply forty people in that location, just the guy put on a stadium bear witness. He came out of a coffin at the beginning, he'due south got this vertically challenged guy, and it's a spectacle. You've got to see it."

VALENTINO: From a visual perspective, he was just starting to develop the persona that exploded, jumping up and down, hair going back and forth, no shirt. Like Anthony Kiedis of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, only dressed in hip-hop attire. He never stopped moving onstage the whole time. It was stunning to see visually.

The live prove was a combination of hip-hop, rock, even some country. There was about a Lynyrd Skynyrd thing going on. In trying to sell this (to record labels), it became clear to me that the rock bending was what really needed to exist stressed.

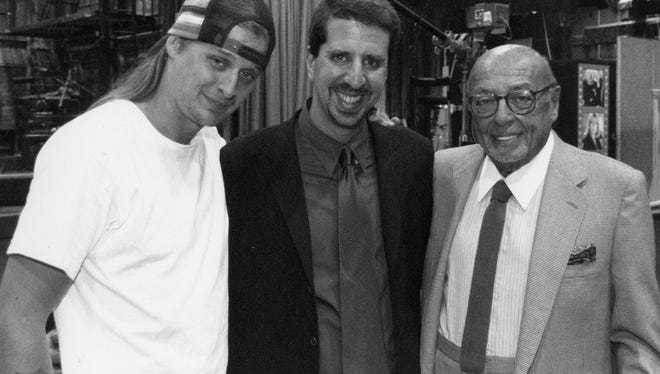

FLOM: We went to Detroit shortly thereafter to see him at the State Theatre. And it was every bit the spectacle that we'd talked about.

Detroit Free Press, May 25, 1997: "When Detroit hip-hop-roots-rocker Kid Stone hits the Country Theatre stage Fri dark, there will be some important sets of ears in the audience. Information technology's a showcase gig, and the major characterization reps are heading into the house to check out the colorful, pounding show from Rock and his coiffure."

Basic: It was a big thing. There was a little more than rehearsing that went on for that one. You lot could feel there was a lot at stake. But it was still a lot of fun — not like a lot of tension or anything. Something just felt like the shit was most to hit.

MARTIN: I was knocked out of my seat at the Country Theatre. It was like watching an explosion. Joe C was up there. The whole presentation was so funfair-like. He's got the savvy of a P.T. Barnum. He mixed those styles, and information technology but worked. It seemed symbolic of irresolute times.

NIEPORTE: Flom pulled me aside and spent one-half an hour drilling me with questions: How well do yous know him, does he practise drugs, is his head on straight? Bob put on a astounding bear witness that day. He got signed because of that gig.

FLOM: After (the prove), we bundled to meet in the basement of some disco club, some crazy place in Detroit. Rock got in that location about two:30 in the morning time. Nosotros sat in that location under the fluorescent lights, a very surreal setting, to talk over what kind of record would he make. After that meeting, he went and laid down a couple of tracks — "Somebody'due south Gotta Feel This" and "I Got One for Ya" — and sent them to us a few weeks later on.

I was in a car in L.A. on Hollywood Boulevard when I put in the ii tracks. I called him immediately and said, "I'll give you lot whatever yous want." We made a deal on the telephone.

His major-label contract in hand, Rock worked on "Devil Without a Cause" through spring 1998, cut tracks at the White Room and polishing the concluding versions at the Mix Room in Los Angeles. Most of the album was cowritten with Kracker.

VALENTINO: Kracker brought a unlike melodic sensibility. Bob could give you all the other stuff, from the beats to the arrangements to the attitude. They developed into a great songwriting team.

KRACKER: I would help writing verses and whatnot. Only more than than anything else, I was his biggest cheerleader and worst critic. If something fell out of his oral fissure and sucked, I'd tell him. That was me being selfish: For me, Bob was probably the closest thing to the kind of music I wanted to listen to. So if he spun something that was dumb, I'd tell him.

Only he's great with melodies and lyrics. And he's swell under pressure.

LEE: You lot could feel it coming, the build-up before "Devil." When guys like (Atlantic Records founder) Ahmet Ertegun and Jason Flom are coming into town, you tin can tell something special is going on.

NEHRA: He took some tracks he'd previously recorded, remixed, overdubbed the vocals. "Bullgod" was an older one. Others he did from scratch — "Cowboy" was a brand new track.

Information technology was an exciting fourth dimension. We knew where Bob was heading.

BASS: Nosotros were with Marshall (Eminem) at the Mix Room in 50.A. (finishing "The Slim Shady LP") at the aforementioned time Bobby was at that place. Marshall wanted these deep vooka-vooka scratches on "My Fault," and then Bobby goes in and does those cuts, while Marshall goes in the other room and writes part of a song for him.

It was absurd because we were both doing these records at the same time, and information technology was starting to feel similar Detroit had it all sewed up.

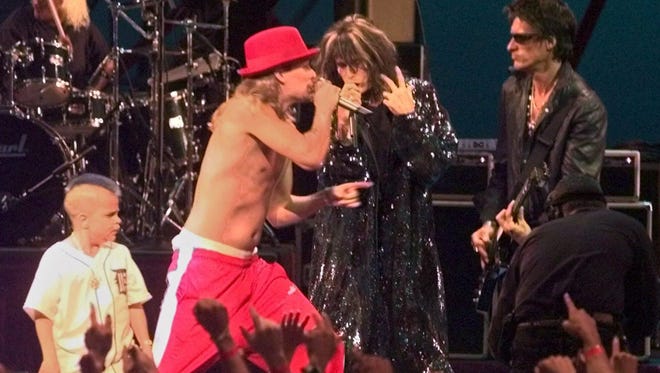

"Devil Without a Cause" was released in Baronial 1998 and, after a slow initial build, exploded onto the national radar thanks to MTV appearances, the radio hits "Bawitdaba" and "Cowboy," and a milestone set at Woodstock '99 televised to a national audience.

FLOM:The first appearance he did on "Fashionably Loud" on MTV (in Dec 1998), he performed "Bawitdaba." That was i where everybody went, uh oh. The tipping bespeak occurred at the MTV Awards (in September 1999) when he did the medley with Run-D.M.C. and Aerosmith. Watching that, I said, "Holy shit." What else could you say?

VALENTINO: When he took the phase at Woodstock, I was so nervous. I said to myself, this is going to be a really, actually big moment. … Simply every minute going by he was killing it more than and more. It was like an athlete in the zone. It was that powerful. He'd been playing out. But really, what he displayed in that show was the savvy of a performer who had done 10 or 12 earth tours.

BASS: I'thou non sure I'll exist hearing (Eminem'south) "My Name Is" on a classic rap station in 20 years. But you'll exist hearing Bobby on classic rock and country. He made it work. Who thought we'd take country music with 808 kicking drums.

LEE: He had come dorsum from New York after Jive with his tail between his legs. Doors were getting slammed in his face. Even around a lot of the music scene in Detroit, he was an outcast. In retrospect, that might have been the best thing to happen to him. The progress he made on his own meant they had to pay attention.

CLARK: That offset time I saw him when he walked into the studio in 1989, nobody knew who the hell he was, and he was carrying himself with and then much confidence.

When he was making "Devil Without a Cause," he played me those first demos, and I listened to him rapping, "I'm going platinum, I'm going platinum." I said, "Come on, human. You haven't sold shit."

But he knew. He close me up. He close everybody up.

Contact Brian McCollum: 313-223-4450 or bmccollum@freepress.com

These are the people whose voices you lot've read in this oral history, and their roles in the 1990s during Kid Rock's early Detroit days.

Mark Bass: His ring Black Planet opened shows for Kid Rock in the early '90s, and Bass went on to a career producing Eminem records as part of the Bass Brothers.

Jimmie Basic: A veteran keyboardist on the Detroit scene who has been part of Twisted Brown Trucker for nearly two decades.

Mike E. Clark: The studio wiz was Child Rock's start producer, and went on to go the main collaborator with Insane Clown Posse.

Thornetta Davis: This longtime R&B singer did backups on early Kid Rock material and his hitting "All Summer Long." Her new album "Honest Woman" is due out this year.

Bob Ebeling: Kid Stone'due south onetime roommate is a drummer and Grammy nominated studio engineer who has worked with Eminem, Phish and others.

Jason Flom: Flom founded Lava Records, which signed Rock in 1998. His signings take included Paramore, Lorde and Matchbox Twenty.

Tino Gross: A blues, funk and stone mainstay in Detroit for more than 30 years, including front homo for the Howling Diablos.

Mike Himes: He opened the get-go Record Time store in 1983 in Eastpointe, with eventual stores in Roseville and Ferndale before endmost in 2011.

Marc Kempf: Kempf was embedded in Detroit'due south 1990s hip-hop scene, managing Eminem and publishing Clandestine Soundz magazine.

Uncle Kracker: His older blood brother was a friend of Kid Rock; Kracker eventually became Rock'due south DJ and right-hand human being.

David Lee: This Detroit attorney (who has not represented Kid Rock) was part of a rolling crew of political party friends with Child Rock and the Howling Diablos.

Scott Legato: Now a nationally published concert photographer, Legato was a lodge DJ in the 1990s.

Joel Martin: This local impresario and studio operator was managing Moog Stunt Team in the '90s when he met Kid Rock. He went on to piece of work closely with Eminem, including managing the rapper'due south vocal publishing.

Michael Nehra: He and his blood brother, Andrew Nehra, founded White Room Studios, working with Large Chief and others, and subsequently formed Robert Bradley'south Blackwater Surprise. Today they run the music-gear company Vintage King.

Joe Nieporte: Managed the Ritz in Roseville, and afterwards the State Theatre. Today he runs Funfest Productions, which manages Freedom Hill and festivals including Stars & Stripes.

Brian Pastoria: Long-tenured drummer with Adrenalin and DC Drive who went on to run the Harmonie Park entertainment complex.

Jerry (Vile) Peterson: Longtime Detroit punk and fine art fixture who founded Orbit mag in 1990.

Brad Shaw: Kid Rock'south get-to lensman in the 1990s, with shots that made the comprehend of "Early Mornin' Stoned Pimp" and "History of Rock."

Vickie Siler: An early Kid Rock fan from Toledo who has since attended more than 70 shows and several Kid Stone cruises.

Al Sutton: Sutton was White Room Studio'southward co-founder and engineer, and went on to offset Rustbelt Studios in Royal Oak. He remains Kid Rock's go-to engineer.

Tommy Valentino: A veteran New York music attorney who helped land Kid Stone'south bargain with Lava/Atlantic in 1997.

1990: The rap album "Grits Sandwiches for Breakfast" is released past Jive.

1991: Kid Stone is dropped by the characterization and returns to Detroit.

1993: "The Polyfuze Method" and "Fire Information technology Up" are released past Continuum.

1994-95: Kid Rock links up with Detroit'south rock scene via White Room Studio and the Bear's Den, and incorporates a live ring into his own shows.

1996: "Early on Mornin' Stoned Pimp" is released on Stone's Top Canis familiaris label.

1997: Atlantic Records executives catch Stone's increasingly sophisticated live prove, sign him to a deal.

1998: "Devil Without a Cause" is released by Atlantic, ultimately selling more than 10 million copies.

At this point, Kid Rock is just padding his ain records.

With 10 shows on tap this month at DTE Free energy Music Theatre — from Friday through Aug. 22 — the Detroit rocker will break historical marks he broke or matched ii years ago.

In 2013, his viii-show run broke Bob Seger'due south 35-twelvemonth-old record for the longest uninterrupted run of dates at the former Pino Knob. Rock also tied Seger for the near shows there in a single summer.

This month'south sold-out stand volition put Kid Rock in front of near 150,000 concertgoers — a number that promoters take called the biggest fix of ticket sales for an artist in Michigan concert history.

It'due south difficult to know for sure if they're right, simply regardless, the statistics smooth: When superstar Garth Brooks sold out six nights earlier this twelvemonth at Joe Louis Arena, his folks proudly trumpeted the fact that his 107,000 ticket buyers broke his own previous record in the state.

Rock volition play DTE on Aug. 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, fifteen, 18, 19, 21 and 22. Tickets are sold out.

Source: https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/music/brian-mccollum/2015/08/26/kid-rock-early-years-detroit/31193049/

Post a Comment for "You re Spinning Me Around in Circles Again That Cute Skinny Blond Girl"